Belief in black magic persists in Papua New Guinea, where communities are warping under the pressure of the mining boom’s unfulfilled expectations. Women are blamed, accused of sorcery and branded as witches — with horrific consequences.

The shout went up from a posse of children as they raced past the health clinic in a valley deep in the Papua New Guinean highlands. Inside, Swiss-born nurse and nun Sister Gaudentia Meier — 40-something years and a world away from the ordered alps of her homeland — was getting on with her daily routine, patching the wounds and treating the sicknesses of an otherwise woefully neglected population. It was around lunchtime, she recalls.

Sister Gaudentia knew immediately the spectacle the excited children were rushing to see. They were on their way to a witch-burning. There are many names for dark magic in the 850 tongues of Papua New Guinea, sanguma resonating widely in these mountains. The 74-year-old sister hurriedly rounded up some of her staff, loaded them in a car and followed the crowd, with a strong foreboding of what she would find.

Two days earlier she had tried to rescue Angela (not her real name), an accused witch, when she was first seized by a gang of merciless inquisitors looking for someone to blame for the recent deaths of two young men. They had stripped their quarry naked, blindfolded her, berated her with accusations and slashed her with bush knives (machetes). The “dock” for her trial was a rusty length of corrugated roofing, upon which she was displayed trussed and helpless. Photographs taken by a witness on a mobile phone show that the packed, inert public gallery encircling her included several uniformed police.

In Papua New Guinea, the Pacific nation just a short boat ride from Australia’s far north, 80 per cent of the 7 million-plus population live in rural and remote communities. Many have little access to even basic health and education, surviving on what they eat or earn from their gardens. There are few roads out, but a burgeoning network of digital-phone towers and dirt-cheap handsets now connect them to the world — assuming they can plug into power and scrounge a few kina-worth of credit.

The beautiful landscape of PNG’s highlands belies the brutal reality of life in the region, where more than 90 per cent of women report suffering gender-based violence.

The beautiful landscape of PNG’s highlands belies the brutal reality of life in the region, where more than 90 per cent of women report suffering gender-based violence.

The resources-rich country is in the midst of a mining boom, but the wealth bypasses the vast majority. In their realities, some untouched by outside influence until only a couple of short-lived generations ago, enduring tradition widely resists the notion that natural causes, disease, accident or recklessness might be responsible for a death. Rather, bad magic is the certain culprit.

“When people die, especially men, people start asking ‘Who’s behind it?’, not ‘What’s behind it?’” says Dr Philip Gibbs, a longtime PNG resident, anthropologist, sorcery specialist and Catholic priest.

Last year, a two-year investigation by the country’s Constitutional and Law Reform Commission observed that the view that sorcery or witchcraft must be to blame for sickness or early death is commonly held across PNG.

Many educated, city-dwelling Papua New Guineans also espouse some belief in sorcery. But in the words of the editor of the national daily Post Courier, Alexander Rheeney, city and country-folk alike overwhelmingly “recoil in fear and disgust” at lynch-mobs pursuing payback, and at the kind of extremist cruelty that Sister Gaudentia was about to witness.

Angela’s accusers — young men from another town, high on potent highlands dope and “steam” (home-brewed hooch) — had come back for her. Sister Gaudentia suspected the same mob had tortured a young woman she nursed a few months earlier. She had dragged herself, “how … I don’t know”, says the nun, into the clinic, her genitals burned and fused beyond functional repair by the repeated intrusions of red-hot irons.

The concept of a serial-offending torture squad hunting down witches doesn’t fit the picture anthropologists have assembled of the customs that underwrite sorcery “pay-back” in parts of PNG. Attacks are, as a general rule, the spontaneous act of a grieving family, inspired often by vengeance, and sometimes by fear that evil magic will be exercised again. But experts also concede there are caveats to every rule in PNG. One of the most ethnically diverse landscapes in the world, PNG is endlessly confounding to outsiders, and even as modern explorers strive to pin down aspects of the old world, it changes before them.

Walne was accused of using sorcery to kill a young boy and hunted by her husband’s family. Narrowly escaping public execution, she is currently in hiding.

Walne was accused of using sorcery to kill a young boy and hunted by her husband’s family. Narrowly escaping public execution, she is currently in hiding.

As more reports of sorcery-related atrocities find their way into the PNG media, United Nations’ forums, and human rights investigations, there are concerns that the profile of this social terrorism is shifting. Ritual attacks on accused sorcerers — historically brutal in some parts, notoriously so in the punishing highlands — appear to have broken out of traditional boundaries, and now crop up in communities where they have no history.

Despite a lack of data and the suspicion that only a fraction of incidents are ever reported, the 2012 Law Reform Commission examination of sorcery-related attacks concluded that they have been rising since the 1980s. It estimated about 150 cases of violence and killings are occurring each year in just one volatile province, Simbu — wild, prime coffee country deep in the nation’s rugged spine. Figures vary enormously but volumes of published reports by UN agencies, Amnesty International, Oxfam and anthropologists provide unequivocal evidence that attacks on accused sorcerers and witches — sometimes men, but most commonly women — are frequent, ferocious and often fatal.

Australian National University anthropologist Dr Richard Eves is a PNG specialist who is convening a conference on the issue in Canberra in June. As he explains, the truism of anthropological literature is that the thrall of sorcery and witchcraft over a society declines with modernity, as occurred in Europe and North America. But right now in Melanesia, and particularly in PNG, this seems not to be the case.

Instead reports indicate tradition has in places morphed into something more malignant, sadistic and voyeuristic, stirred up by a potent brew of booze and drugs; the angry despair of lost youth; upheaval of the social order in the wake of rapid development and the super-charged resources enterprise; the arrival of cash currency and the jealousies it invites; rural desperation over broken roads; schools and health systems propelling women out of customary silence and men, struggling to find their place in this shifting landscape bitterly, often brutally, resentful.

“I have been in PNG since 1969,” says Sister Gaudentia. “We always had sanguma, but not to the extreme, not like it is now.”

Gibbs, who has published many articles on the issue, agrees that attacks have become more brutal. “It used to be that they would push someone over a cliff, something like that. They still ended up dead, but it wasn’t the torture, like now. This interrogation, this public stuff, with the kids watching, it becomes a spectacle.”

On the first day of Angela’s agonies, the nun pleaded with the watching police to intervene. Why would they and other community leaders not act? Gibbs explains: “Even if they would want to stop the violence, they have little power today in the face of a village mob — particularly when many young men within the mob are affected by alcohol or drugs”.

These men call their gang “Dirty Dons 585” and admit to rapes and armed robberies in the Port Moresby area. They say two-thirds of their victims are women.

These men call their gang “Dirty Dons 585” and admit to rapes and armed robberies in the Port Moresby area. They say two-thirds of their victims are women.

PNG’s police force is underpaid, under-resourced and under-trained. It’s also notoriously corrupt and abusive. Many members subscribe to sorcery belief and some may see the interrogation of women like Angela as legitimate under custom, a view some argue is encouraged by the controversial PNG Sorcery Act of 1971, which acknowledges the existence of sorcery and criminalises both those who practice it and those who attack people accused of sorcery.

On that opening day of her “trial”, Angela was tortured, humiliated and interrogated; an absurd Monty Python-esque parody of prosecution in which she was in one moment accused of causing the deaths, the next being asked to give up the name of the real witch — “kolim nem, kolim nem [call the name]”, the gang demanded. At one point, in wracked desperation, she shouted out the name of another woman, but her accusers showed no interest.

For reasons not clear, they let her go, and the next day Sister Gaudentia heard she had been taken to a holding room at the police station, apparently for her safety. The nun tried to see her but the room was locked and no-one could locate the key. “I thought she was safe.” She later learned that at some point the police had released Angela after her attackers signed pledges to leave her alone.

It was lunchtime the next day when Sister heard the children’s chilling chorus outside the clinic window. “I left the car up the road and then we went into the village. At least we tried to go in,” the Sister recalls. The crowd was so dense she couldn’t push through. “I went back to the car and drove to the police station to report that they were torturing her again. The police commander said, ‘We can’t do anything. They promised me they wouldn’t.’”

Sister drove back, taking a priest with her. This time they fought their way through. “There must have been 600 people watching; men, women and children — a lot of them.”

Angela was naked, staked-out, spread-eagled on a rough frame before them, a blindfold tied over her eyes, a fire burning in a nearby drum. Being unable to see can only have inflated her terror, her sense of powerlessness and the menace around her; breathing the smoke and feeling the heat of the fire where the irons being used to burn her were warmed until they glowed. Would she be cooked, on that fire? She must have known it had happened to others before — and would soon infamously happen again, the pictures finding their way around the world.

The photographs witnesses took of Angela’s torture are shocking, both for the cruelty of the attackers and the torpid body-language of the spectators. Stone-faced men and women and wide-eyed children huddle under umbrellas, sheltering from the drenched highlands air as Angela writhes against the tethers at her wrists and ankles, twisting her body away from the length of hot iron which a young man aims at her genitals. [The photograph of Angela accompanying this article, taken on the first day of Angela’s torture, is confronting, but chosen as less humiliating and dangerous than pictures taken on the second day which would identify key individuals.]

Angela — a woman in her late 40s — is the mother of a small boy, says Philip Gibbs, who later collected her testimony and that of witnesses to her ordeal. Typical of the victims of sorcery-related attacks and killings in the highlands, she had been existing on the margins of her community. She had no husband or male family to protect her. Custom often requires women to leave behind the safe enclave of their own place and family when they marry. If their husband dies or leaves or abuses them, they find themselves stranded on “foreign” soil. As Gibbs has documented in his published work, which delves into the dynamics of accused and accusers, “when a family, believing that death comes through human agency, looks for a scapegoat to accuse, fingers will very often point at a woman without influential brothers or strong sons”.

Sister Gaudentia shouted over Angela’s screams, part begging, part ordering the interrogators she calls “the marijuana boys” to cease their assaults. “They held me back, stopped me getting to her,” she says. When Gibbs later investigated, he learned that the nun had put herself at dire risk — the torturers had tried to burn her, too. It was perhaps only her pale expat skin that saved her.

When there was nothing more she could do to stop Angela’s torment, the Sister gathered her clinic staff around her and shouted out to the crowd. “I called on the people. I asked, ‘Who here is a Catholic? Come, we will pray the rosary.’

“And a lot of people came and prayed with me. We prayed the whole rosary.” Angela’s suffering echoed around them through their invocation, the ritual comforts of one belief system colliding with the atrocities of another.

“A man came from another village and drove us back to the police and we pleaded with them again to come,” Sister recalls. She was still at the station when Angela was cut down. By then there was heavy rain falling. Perhaps the fire had gone out. Perhaps some of the sport had been dampened. Perhaps police did intervene.

It was around 5pm when “the marijuana boys” let Angela go, more than four hours after they began their assaults. When Angela’s elderly mother tried to attend to her they set upon her too, breaking her leg and her pelvis.

Later a police car delivered Angela and her mother to Sister Gaudentia’s clinic. “We treated them that night. People came to our house and wanted us to send these women out, but we didn’t.”

Then the mob grew and began shouting and throwing stones on the clinic roof, and Sister called the police, fearing the clinic would be burned down. “This time a different policeman came, he was really concerned. We had to agree to let the women go to the police cell for their own protection. We took them food.”

With that officer’s help, they smuggled Angela and her mother away by car, taking them a long way away, eventually finding them care in another hospital. When their physical wounds were healed, she was relocated again. She has now joined the ranks of sorcery survivors who are not only damaged but forever displaced by their experiences, refugees within their own country, forced away from the land many of them rely on for survival.

She remains in hiding with her young son.

Dini was accused of using black magic to kill her son. His friends dragged her to a pigsty, where she was tortured using bush knives and red-hot iron bars.

Dini was accused of using black magic to kill her son. His friends dragged her to a pigsty, where she was tortured using bush knives and red-hot iron bars.

ON FEBRUARY 7, Papua New Guineans woke to the headline “Burnt Alive!” and pictures of a large crowd, including school children, watching as flames engulfed the body of a young woman.

It happened in the busy, mercurial hub of Mount Hagen, smack in the heart of the country. A 20-year-old mother of two, Kepari Leniata, had been stripped, tortured, trussed, doused with petrol, thrown on a rubbish tip, covered with tyres and set alight.

The killing was reportedly carried out by relatives of a six-year-old boy who had just died in the local hospital. They seized a couple of women they suspected of causing the death, among them Leniata, and soon determined that she would be the scapegoat of their grief. Witnesses claimed the crowd blocked police officers and firefighters who tried to intervene.

The news provoked a statement of “deep concern” from the UN human rights office and international media coverage. PNG Prime Minister Peter O’Neill condemned the killing as a “despicable” and “barbaric” act. He said he had instructed police to use all available manpower to bring the killers to justice.

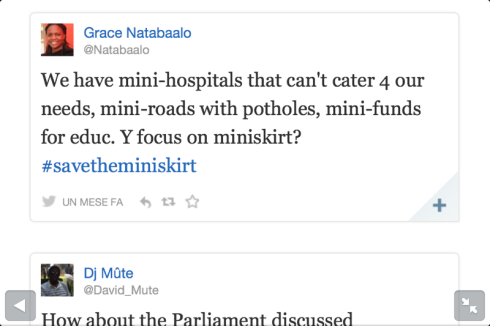

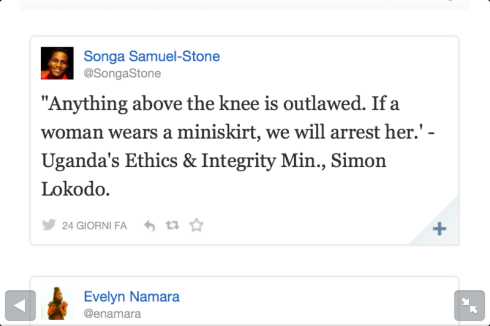

“It is reprehensible that women, the old, and the weak in our society, should be targeted for alleged sorcery or wrongs that they actually have nothing to do with,” said O’Neill. Similar sentiments resounded across PNG’s always animated social media scene, and included a push for a campaign to enlist Leniata’s name and legacy to rally momentum to address endemic, epidemic violence against women.

Leniata’s death and the anguish it provoked reprised a very similar scenario only two years ago, also on a rubbish tip in Mount Hagen, when an unidentified young woman — according to some reports, possibly as young as 16 — was tied at the stake and burned. But this time there were pictures. The horror of the act, and the passivity of the watching crowd, sent shockwaves across the country.

As the Post Courier’s Rheeney editorialised, the failure of witnesses to intervene, “to stop and condemn the murderers’ actions, points to a bigger danger of ordinary Papua New Guineans accepting this callous killing as normal and this methodology of dispensing justice as acceptable.

Dini shows wounds she received after she was accused of using sorcery to kill her own son.

“Respect for the rule of law and the rights of others are pillars of a modern-day democracy, and we would like to think PNG falls under this category,” he wrote. Leniata’s murder raised questions, he noted, about whether “we believe that justice is dispensed in a legally constituted court of law and not a kangaroo court chaired by individuals misled by superstition and trickery”.

The earlier witch-burning at Mount Hagen, in January 2009, had been the catalyst for the Government’s directive to the PNG Constitutional and Law Reform Commission to review sorcery violence and the legal issues around it. Community distress had peaked following a series of similar reports, including that people accused of sorcery had been roasted over slow fire, nailed to crosses, hung in public places and beaten to death, locked inside homes and set alight, weighted with stones and thrown into rivers, and hacked to death with machetes.

Now Rheeney’s editorial echoed the view of many PNG commentators and international human-rights groups when it urged the Government to at least pursue one powerful, urgent measure and fast-track the key recommendation to emerge from the review: repeal the Sorcery Act.

The 1971 Act, in its preamble, acknowledges “widespread belief throughout the country that there is such a thing as sorcery, and sorcerers have extra-ordinary powers that can be used sometimes for good purposes but more often bad ones”. It distinguishes “innocent sorcery”, defined as protective and curative, from “forbidden sorcery” — everything else.

The Act, the review explains, was largely aimed at recognising the reality of citizens’ concerns and to provide a mechanism for them to have an accused sorcerer dealt with by the courts rather than taking the law into their own hands. Extensive consultations out in the PNG provinces over the past two years revealed that many communities still wanted the law to recognise that sorcery was real and active, and to provide systems to prosecute and punish sorcerers and their accomplices.

As the late Sir Buri Kidu, PNG’s first national Chief Justice, observed in a judgment in 1980, “in many communities in Papua New Guinea belief in sorcery and its powers is very strong and we cannot brush it aside. My own people believe it and greater fear is caused by such belief.” (His Australian-born widow — Dame Carol Kidu, for many years the only woman in the PNG Parliament until her recent retirement — has recounted the story that every night of her young married life in the family’s village home, Buri’s mother would pull the shutters to keep out what in her language they called the “vada”, only to have Buri get up in the small hours and open them again.)

Vlad Sokhin

The review concluded that the Sorcery Act had plainly not prevented bad magic, and nor had it punished practitioners. What it had done was provide legal refuge for murderers and vigilantes to argue sorcery as a mitigating factor, allowing self-styled witch-killers — and comparatively few have even been prosecuted — to get off with light sentences.

After examining various options for amending the Act, the Commission has recommended its repeal, but with provision for village courts to continue to deal with sorcery disputes. It has drafted a Bill to that effect that commission secretary, Dr Eric Kwa, hopes will go before the PNG Parliament in the next few months.

“I’m really appalled by the [latest] reports,” Kwa told The Global Mail. “It is really sickening that Papua New Guineans are not able to stand up for the weak and vulnerable to oppose this evil in our society. We hope that with the repeal of the Sorcery Act [if the recommendation is supported], the normal criminal liabilities will apply in terms of serious crimes such as the one we read of today.”

Many commentators argue it will take much more than a change in legislation to achieve any meaningful inroads against the violence. Anthropologist Philip Gibbs, whose archive of work was heavily drawn on by the Law Reform Commission review, is one of them.

At the national level he urges the Government to also set up a PNG human-rights council — a measure promised in the past — and to consider establishing special police task forces to pursue killers. Human rights and UN agencies have repeatedly slammed PNG police for failing to intervene to stop attacks or to arrest suspects. But they also recognise the besieged force requires monumental investment in training, resources and equipment if it is to be effective.

As one 2011 UN report summarised, the PNG constabulary lacks everything from adequate pay, uniforms and accommodation to leadership. As a consequence, corruption is rife and morale poor. Police have almost no intelligence-gathering capacity. The likelihood of criminals being caught has been estimated at less than 3 per cent.

Even assuming the political will emerges to invest in stronger policing and community protection, it will be years before the terrorism fades in communities like Simbu, an epicentre for violence. Aid and development agencies have also been reluctant to touch the issue, says Richard Eves. “For many years religion was a taboo for donor agencies. Because it is so cultural and so complex, it’s not easy to come up with projects to address it.”

In the meantime concerned citizens, local human-rights activists and churches — deeply engaged with their congregations, and often the only functional institutions in sight — are devising grassroots interventions, some of them with substantial effect, according to Gibbs.

One such program is championed by Bishop Anton Bal, the Catholic bishop of Kundiawa, the capital of Simbu. Born and raised in the province’s remote south, he’s enlisting his networks and his understanding of the culture to find ways to infiltrate and change thinking. Working with him is Polish-born surgeon and priest Father Jan Jaworski, whose work in the community as a healer of body and soul over more than 25 years resonates widely, earning authority.

Through its close connections to families the diocese is able to measure the reverberating damage from sorcery violence. The casualties number many more than the dead. The bishop’s office has estimated that as much as 10 to 15 per cent of the population have been displaced by fallout from accusations and attacks, many of them banished, their homes and sustaining gardens destroyed.

Bishop Bal argues that the catch-22 with sorcery is that the more it’s talked about, the greater its power and allure. So his programs include training up networks of local parish volunteers as a kind of resistance movement. Operatives deflect and douse conversations about blame as soon as a death in the community occurs. They go to the funeral and when someone brings up the question of sanguma they shift the topic — talk about the weather, shut it down. Or raise the alarm.

Kundiawa is in name a provincial capital, but in reality a pit stop on the nation’s only east-west thoroughfare, the Highlands Highway, which is heavily trafficked and rapidly eroding under the wheels of fortified convoys running to and from mine sites. It’s also the trading post and heart of a far-flung society of hamlets sprinkled through some of PNG’s steepest, tallest, harshest and lushest ranges.

At Kundiawa Hospital, which is distinguished by the proud efforts of its staff and community as something of a showpiece within PNG’s weary provincial hospital network, Jaworski sees patients with sorcery-related trauma being admitted at least a couple of times a week. “[They’re] usually women, but not only. It’s the tip of the iceberg. It is still very strong [the belief]. It is part of the system of justice.” After so many years at sanguma ‘Ground Zero’, there’s not much that shocks him.

Part of his practice is to use the influence he has gained to interrupt the cycle of accusation and prosecution, to go to the grieving family and explain medical cause of death whenever he has the opportunity, and pray that his story finds its way onto the bush telegraph and around the district.

Vlad Sokhin

Not long ago the brother of a local politician died. When Jaworski got word that some 300 family members had gathered and were milling about looking for someone to blame, he went and confronted the mob. “I told them [his death] was his own responsibility. He was a fat man. He didn’t look after himself. Sometimes you have to put the responsibility on the person who has gone, or it hurts someone else.”

On another occasion he confronted the family of a young woman who had died of HIV/AIDS. When she was still a girl the family had given her to an older man in the community. She became his third wife, and then she became infected and sickened, leaving behind a young baby. “I told them ‘It is your fault she died — not sanguma. You sold her as a third wife.’ I wanted to burden them with the responsibility, otherwise they will just accuse someone else.

“The uncle stood up and said, ‘Thank you for providing the explanation — we will not go for sanguma’. It was a hard thing for the family to hear’ — and, the priest admits, a nerve-wracking thing to say to a riled Simbu family — “but otherwise some innocent will be tortured and killed.”

Anecdotal testimony, discreetly shared, points to a substantial and growing underground movement of self-proclaimed human-rights defenders working within communities to identify and hide people who are at risk of attack, or who have survived. In some of the most fraught parts of the highlands aid agency Oxfam engages in a range of programs that support some of those evolving networks.

But people operate in this sphere do so at some personal risk. In a locally infamous case in 2005 highlighted by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Anna Benny, a woman in Goroka who had a reputation for fearless work protecting and supporting rape victims, tried to defend her sister-in-law from allegations of sorcery. Both women were killed. Police took no action.

Vlad Sokhin

In his interviews surveying survivors of sorcery-violence, including Angela — the woman likely rescued by the intervention of Sister Gaudentia and some heavy rain — Philip Gibbs identifies a consistent, fortifying thread. Those victims who lived to tell the tale owe their lives either to individual police members or to a strong church leader who intervened for them. “In effect it means that, if sufficiently motivated to act, the power of the police and civil authorities, or the power of the church, can be enough to defend a person who is otherwise powerless.”

Supporting people with the will and courage to exercise their power at the grassroots to tackle violence in any of its manifestations — domestic, social, sorcery-related — is the focus of Bal and Jaworski. Parables of successful interventions become their currency of hope. But they admit they are often despairing.

Jaworski blames much of the escalating violence in all spheres on deeper social malaise, in particular the angry frustrations of young men, and for which there are no easy remedies. “Today 70 to 90 per cent of young people are unemployed. They went to school, but there is no future for them. They don’t fit back in their gardens and their villages.” They are without prospects in the new world, and without skills for the old one.

On bleaker mornings, navigating broken roads strewn with rocks from a night of fighting, or stitching up the casualties in the operating theatre, Jaworski worries that the rage of young men will one day propel the community back to the tumbuna (the time of the ancestors).

“I hope I am a wrong prophet.”